8 Searching the literature

Step 1: Get organized

The process of searching databases and revising your working question can be time-consuming, so it is a good idea to write notes to yourself. Remembering why you included certain search terms, searched different databases, or other decisions in the literature search process can help you keep track of what you’ve done. You can then recreate searches to download articles you may have missed or remember reflections you had weeks ago when you last conducted a literature search.

Activity:

- Create a Research Journal to record notes and reflections on the search process, including keywords and terms.

- Create a folder or use a document management tool (e.g., Zotero) to create a library of articles to review for your research.

- Build a spreadsheet with basic article information for easy reference: author, title, abstract, key findings relevant to your work. You may choose to create an Annotated Bibliography or Thematic Analysis Grid to help you manage the large amount of information you’re collecting for easy use later in the writing process. These techniques are explained in more detailed in subsequent chapters.

Step 2: Build search queries using keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something in a search engine like Google Scholar or your university Library? What you type into a database or search engine is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need more quickly, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want.

Keywords are the words or phrases you use in your search query, and they inform the relevance and quantity of results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different terms to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as testing, rather than assessment (for example). Think about what keywords are important to answering your working question. Are there other ways of expressing the same idea?

Often in education research, there is a bit of jargon to become familiar with when crafting your search queries. For example, if you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include the word “parentification” as part of your search query. You are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. As you read more about your topic and become familiar with some of these words, begin including these keywords into your search, as they may return more relevant hits. In some articles, there will be a list of keywords after the abstract, or you can pick them out of the abstract for further follow up.

Activity:

- List all of the keywords you can think of that are relevant to your working question.

- Add new keywords to this list as you are searching and learn more about your topic.

- Add to your Research Journal by recording your keywords as well as your notes and reflections on the search process.

Boolean search operators

Databases that are important for education research—such as Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, and Education Source—will not return useful results if you ask a question or type a sentence or phrase as your search query. Instead, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “what are the effects of class size reduction on student behaviour,” you might type: “class size” AND “behaviour”.

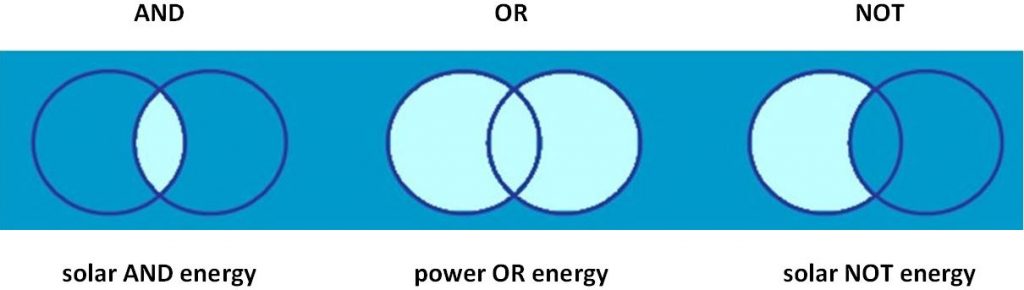

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “class size” AND “behaviour” returns articles that mention both class size and behaviour. There are lots of articles on class size and lots of articles on behaviour, but fewer articles that address both of those topics. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present.

The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to class size at the post-secondary level. Searching for “class size” AND “behaviour NOT “undergraduate” or “class size” AND “behaviour NOT “graduate” would exclude articles that mentioned undergraduate or graduate students. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “class size” OR “behaviour” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in the figure below.

Activity:

- Build a simple Boolean search query, appropriately using AND, OR, and NOT.

- Experiment with different Boolean search queries by swapping in different keywords.

- Write down which Boolean queries you create in your Research Journal.

Step 3: Find the right databases

Queries are entered into a database or a searchable collection of information. In research methods, we are usually looking for databases that contain academic journal articles. Each database has a unique focus and presents distinct advantages or disadvantages. It is important to try out multiple databases, and experiment with different keywords and Boolean operators to find the most relevant results for your working question.

Google Scholar

The most commonly used public database of scholarly literature is Google Scholar, and there are many benefits to using it. Most importantly, Google Scholar is free and is the only database to which you will have access after you graduate. Building competence at using it now will help you as you engage in the evidence-based practice process post-graduation. Google Scholar also understands Boolean search terms and contains some advanced searching features like searching within one specific author’s body of work, one journal, or searching for keywords in the title of the journal. The ‘Cited By’ field, which counts the number of other publications that cite the article, and a link to explore and search within those citing articles, is a useful tool. This can be helpful when you need to find more recent articles about the same topic.

You can also set email alerts for a specific search query, which can help you stay current on the literature over time, and organize journal articles into folders. If these advanced features sound useful to you, consult Google Scholar Search Tips for a walk through.

While these features are great, there are some limitations to Google Scholar. The sources in Google Scholar are not curated by a professional body like the American Psychological Association (who curates PsycINFO). Instead, Google crawls the internet for what it thinks are scholarly works and indexes them in their database. When you search in Google Scholar, the sources will be not only journal articles, but books, government and foundation reports, gray literature, graduate theses, and articles that have not undergone peer review. There is no way to select for a specific type of source, and you need to look clearly and identify what kind of source you are reading. Not every source on Google Scholar is reputable or will match what you need for an assignment.

With that broad focus, Google Scholar ranks the results from your query by the number of times each source was cited by other scholars and the number of times your keywords are mentioned in the source. This biases the search results towards older, more foundational articles. So, you should consider limiting your results to only those published in the last few years. Unfortunately, Google Scholar also lacks advanced searching features of other databases, like searching by subject area or within the abstract of an article, which are tools you can find using your university’s Library database.

The last major limitation of Google is that the articles returned are often held behind paywalls. A great work around is to simply paste the title into your university’s Library search window.

Activity:

- Type your queries into Google Scholar. See which queries provide you with the most relevant results.

- Look for new keywords in the results you find, particularly any jargon used in that topic area you may not have known before. Write down notes on which queries and keywords work best in your Research Journal.

- Reflect on what you read in the abstracts and titles of the search results in Google Scholar.

Databases accessed via an institution

Although learning Google Scholar is important, you should take advantage of the databases to which your university Library purchases access. The first place to look for education scholarship is Education Source, as this databases is indexed specifically for the discipline of education. As you are aware, Education is interdisciplinary by nature, and it is a good idea not to limit yourself solely to the education literature on your topic. If your study requires information from the disciplines of psychology, social work, or medicine, you will likely find the databases PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and PubMed (respectively) to be helpful in your search.

There are also less specialized databases that contain articles from across education and other disciplines. Academic Search Premier is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines. Within Academic Search Premier, you can click Choose Databases to select databases that apply to different disciplines or topic areas.

Many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches some of the databases to which they have access, including both disciplinary and interdisciplinary databases. Meta-search engines are fantastic, but you must be careful to narrow your results down to the type of resource you are looking for, as they will include all types of media (e.g., books, movies, games). Unfortunately, not every database is included in these meta-search engines, so you will want to try other databases, as well.

You can find the databases we mentioned here and others on the Databases page of your university library. A university login is required to for you to access these databases because you pay for access as part of the tuition and fees at your university.

Activity:

- Explore different databases you can access via your university’s library website and searching using your keywords.

- Write notes on which databases and keywords provide you with the most relevant results and the disciplines you are likely to find in each database.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 4: Reduce irrelevant search results

At this point, you should have worked on a few different search queries, swapped in and out different keywords, and explored a few different databases of academic journal articles relevant to your topic. Next, you have to deal with the most common frustration for students: narrowing down your search and reducing the number of results you have to look at. You should have two goals in reducing the number of results:

- Reduce the number of sources until you could reasonably skim through the title and abstract of each source. Generally, you want a hundred or a thousand results, rather than a hundred thousand results.

- Reduce the number of irrelevant sources in your search results until you are much more likely to encounter relevant, rather than irrelevant articles. If only one of every ten results in your search is relevant to your topic for example, you are wasting time. You would be better served by using the tips below to better target your search query.

Here are some tips for reducing the number of irrelevant sources when you search in databases.

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “class size” or “teacher quality.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics that mention your search term only once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE, but that may be too restrictive, and exclude relevant articles with titles that use slightly different phrasing. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use SUBJECT headings to find relevant articles. These tags are added by the organization that provides the database, like the American Psychological Association who curates PyscINFO, to help classify and categorize information for easier browsing.

- Narrow down the years of publication. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful. They no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year. Check with your professor to see if they have specific guidelines for when an article is “too old.” Note however that foundational articles are likely to be older publications, so make sure to search for both.

- Click the limiters of “full text” and “peer reviewed” to narrow the results (after all, you want to be able to read the full article and they should be from peer reviewed sources.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know, and they are extensively trained in how to help you!

- Talk to someone knowledgeable about your target population. They have lived experience with your topic which can help you understand the literature through a different lens. Moreover, the words they use to describe their experiences can also be useful sources of keywords, theories, studies, or jargon.

Activity:

- Using the techniques described in this subsection, reduce the number of irrelevant results in the database queries you have performed so far. Pay particular attention to searching within the abstract, using quotation marks to indicate keyword phrases, and exploring subject headings relevant to your topic.

- Reduce your database query results down to a number where you could reasonably skim through the titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles and where you are much more likely to encounter relevant, rather than irrelevant articles.

- Write down your queries or save them, so you can recreate them later if you need to return to them.

- Also, write down any reflections you have on the search process.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search better, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 5: Conduct targeted searches

Another way to save time when searching for literature is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles: review articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reviewing and reading articles they cited in their references. Other types of reviews such as critical reviews may offer a viewpoint along with a birds-eye view of the literature.

Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” as keywords in your search queries. That said, be careful not to uncritically accept the results reported in these articles – there are ways that meta-analyses can be manipulated.

Read a review article first, before any type of article. The purpose of review articles is to summarize an entire body of literature in as short an article as possible. This is exactly what students who are learning a new area need. Time is a precious resource for students, and review articles provide the most knowledge in the shortest time. Even if they are a few years old, they should help you understand what else you need to find in your literature search.

As you look through abstracts of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors keep appearing. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine.

A similar process can be used for journal names. As you are going through search results, you may also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. You can do so within any database that indexes the journal, like Google Scholar, or through the search feature journal’s webpage. Browse the abstracts and download the full-text PDF of any article you think is relevant.

Step 6: Explore references and citations

The last thing you’ll need to do in order to make sure you didn’t miss anything is to look at the references in each article you cite. If there are articles that seem relevant to you, you may want to download them. Unfortunately, references may contain out-of-date material and cannot be updated after publication. As a result, a reference section for an article published in 2014 will only include references from pre-2014.

To find research published after 2014 on the same topic, you can use Google Scholar’s ‘Cited By’ feature to do a future-looking search. Look up your article on Google Scholar and click the ‘Cited By’ link. The results are a list of all the sources that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar also allows you to search within these articles—check the box below the search bar to do so—and it will search within the ‘Cited By’ articles for your keywords.

Activity:

- Examine the search results and look for authors and journals that publish often on your topic.

- Conduct targeted searches of these authors and journals to make sure you are not missing any relevant sources. Identify at least one relevant article, preferably a review article.

- Look in the references for any other sources relevant to your working question.

- Search for the article in Google Scholar and use the the ‘Cited By’ feature to look for additional sources relevant to your working question.

- Search for review articles that will help you get a broad sense of the literature. Depending on your topic, you may also want to look for other types of articles as well.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

- Write notes on your targeted searches in your Research Journal, so you can recreate them later and remember your reflections on the search process.

Skimming the literature

Not every article you pick up will be relevant to your topic.

For a class assignment, the average literature review will only require that you read 12 to 15 articles in great detail from start to finish. But! You will need to scan and skim at least twice as many articles to discover the ones that are the most relevant to your topic and research question.

Raul Pacheco-Vega recommends using the AIC approach: read the Abstract, Introduction, and Conclusion. For non-empirical articles, it’s a little less clear but the first few pages and last few pages of an article usually contain the author’s reading of the relevant literature and their principal conclusions. You may also want to skim the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Skimming like this gives you the general point of the article, though you should read in detail the most valuable resource of all—another author’s literature review.

Make the most out of the articles you do read by extracting as many facts as possible from each. You are starting your research project without a lot of knowledge of the topic you want to study, and by using the literature reviews provided in academic journal articles, you can gain a lot of knowledge about a topic in a short period of time. This way, by reading only a small number of articles, you are also reading their citations and synthesis of dozens of other articles as well.

Getting the right results

I read a lot of literature review drafts that say “this topic has not been studied in detail.” Before you come to that conclusion, make an appointment with a librarian. It is their job to help you find material that is relevant to your academic interests.

Let’s walk through an example. Imagine a local university wherein smoking was recently banned, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers. Students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two. Their activism was surprising. They were advocating for the freedoms of people committing a deviant act—smoking—that is highly disapproved of. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs?

The student researcher began their research by attempting to familiarize themselves with the literature. They started by looking to see if there were any other student smoke-outs using a simple Google search. When they turned to the scholarly literature, their search in Google Scholar for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on their topic, they informed the professor that they would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for them to review. What went wrong here?

The student had been too narrow in their search for articles in their first attempt. They went back to Google Scholar and searched again using queries with different combinations of keywords. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs” they tried, “college student activism,” “smoke-out,” “protest,” and other keywords. This time their search yielded many articles. Of course, they were not all focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but the results addressed their population of interest, college students, and on their broad topic of interest, activism. Experimenting with different keywords across different databases helped them get a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary view of the topic.

Reading articles on college student activism might give them some idea about what other researchers have found in terms of what motivates college students to become involved in activist efforts. They could also play around with their search terms and look for research on activism centered on other sorts of activities that are perceived by some to be deviant, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, they needed to broaden their search about college student activism to include more than just smoke-outs and understand the theory and empirical evidence around student activism.

Once they searched for literature about student activism, they could link it to their specific research focus: smoke-outs organized by college student activists. What is true about activism broadly is not necessarily true of smoke-outs, as advocacy for smokers is unique from advocacy on other topics like environmental conservation. Engaging with the sociological literature about their target population, college students who smoke cigarettes, for example, helped to link the broader literature on advocacy to their specific topic area.

Revise your working question often

Throughout the process of creating and refining search queries, it is important to revisit your working question. In this example, trying to understand how and why the smoke-out took place is a good start to a working question, but it will likely need to be developed further to be more specific and concrete. Perhaps the researcher wants to understand how the protest was organized using social media and how social media impacts how students perceived the protests when they happened. This is a more specific question than “how and why did the smoke-out take place?” though you can see how the researcher started with a broad question and made it more specific by identifying one aspect of the topic to investigate in detail. You should find your working question shifting as you learn more about your topic and read more of the literature. This is an important sign that you are critically engaging with the literature and making progress. Though it can often feel like you are going in circles, there is no shortcut to figuring out what you need to know to study what you want to study.

Activity:

- Reflect on your working question. Consider changes that would make it clearer and more specific based on the literature you have skimmed during your search.

- Describe how your search queries address your working question and provide a comprehensive view of the topic.

search terms used in a database to find sources of information, like articles or webpages

the words or phrases in your search query

a searchable collection of information