6 Critically reviewing the literature

Information privilege

The core skill you are developing is information literacy, which is key to the lifelong learning process of education practice, as you will have to continue to absorb new information after you leave school and progress as an educator. Education researchers dedicated to social change embrace a more progressive conceptualization of this skill called critical information literacy. It is not enough to simply know how to use the tools we use to share knowledge. Instead, education researchers should critically examine “the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory & Higgins, 2013, p. ix).[1] Just like all other social structures, those we use to create and share knowledge are subject to the same oppressive forces we encounter in everyday life, such as racism, sexism, and classism. Critical information literacy combines both fine-tuned skills for finding and evaluating literature as well as an understanding of the cultural forces of oppression and domination that structure the availability of information.

From critical information literacy, we get the term information privilege which is defined by Booth (2017)[2] as:

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access. Individuals with the resources to access the information they need, are affiliated with research or academic institutions and libraries, or live close to a public library with access to resources and services such as free interlibrary loan are examples of those with information privilege. Those who are unable to access the information they need are information underprivileged or impoverished [emphasis in original]; this includes people who are incarcerated, poor, unaffiliated with a university or research institution, or live in rural areas distant from a public library.

It is important to recognize your own information privilege and use it to help enact social change on behalf of those who are oppressed within the system of scholarly knowledge production and sharing we currently have. For example, paywalls lock away access to knowledge to only those who can afford to pay, shutting out those with fewer resources. This effect of publishing primarily in journals that require a paywall is endemic to university scholarship in general, as Robinson-Garcia and colleagues (2020)[3] note, the “median share of publications openly available of universities worldwide is 43%”, with publications from researchers at Canadian institutions falling below even that low figure. The reasons for this are not financial, as authors do not profit from the sales of journal articles. Indeed, faculty who edit, review, and author articles are not paid for their work under the current model of commercial journal publication. Scholars do not have a meaningful share in the 31.3% profit margins of Elsevier, the largest commercial publisher of scholarly journals (RELX, 2019).[4] Libraries are struggling to keep up with annual price increases.

As Willinsky (2006) states, “access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend, as well as to advocate for, other rights.” The open access movement is a human rights movement that seeks to secure the universal right to freely access information in order to produce social change. Information is a resource, and the current approach to sharing that resource—the key to human development—excludes many oppressed groups from accessing what they need to address matters of social justice. Appadurai (2006)[5] conceptualizes this as a “right to research…the right to the tools through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as citizens” (p. 168). From a human rights perspective, research is not something confined to professional researchers but “the capacity to systematically increase the horizons of one’s current knowledge, in relation to some task, goal or aspiration” (p. 173).

This imbalance between academic researchers and community members should be considered within an English-speaking, Western context. The widespread adoption of open access and open science in the developing world underscores the extreme imbalances that international researchers face in accessing scholarly information (Arunachalam, 2017).[6] Paywalls, barriers to international travel, and the tradition of in-person physical conferences structure the information sharing practices in social science in a manner that excludes participation from researchers who lack the financial and practical resources to access these exclusionary spaces (Bali & Caines, 2016; Eaves, 2020).[7]

In the Canada, the federal government has increasingly adopted policies that facilitate open access, including the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) requirement that all publications from projects they fund must be open access within a year after publication in a commercial journal. The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) has been working with the U.S. presidential administrations on a formal proposal to make all research articles published using federal grant funds accessible to the public as open access, though at the time of this writing there was no final agreement on the policy design or implementation. In Europe, Plan S is a multi-stakeholder social change coalition that is seeking structural change to scholarly publication and open access to research. Latin America and South America are far ahead of their Western counterparts in adopting open access, providing a view of what is possible when community and equity are centered in scholarly publication (Aguado-Lopez & Becerril-Garcia, 2019).[8]

The current model of scientific publishing privileges those already advantaged and raises important obstacles for those in oppressed groups to access and contribute to scientific knowledge or research-informed social change initiatives. For a more thorough, Black feminist perspective on scholarly publication see Eaves (2020).[9] As educators, it is your responsibility to use your information privilege—the access you have right now to the world’s knowledge and the skills you gain during your graduate education and post-graduate professional development—to fight for social change.

Being a responsible consumer of research

When assessing social scientific findings, think about the information provided to you. Social scientists should be transparent with how they collected their data, ran their analyses, and formed their conclusions. These methodological details can help you evaluate the researcher’s claims. If, on the other hand, you come across some discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper, chances are that you will not find the same level of detailed information that you would find in a scholarly journal article. With secondary sources like news articles, it is hard to know enough about the study to be an informed consumer of information. Always read the primary source when possible.

Additionally, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most funders want, and in fact require, that recipients acknowledge them in publications. Keep in mind that some sources may not disclose who funds them. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the internet to see if you can learn more about the funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less influence on your thinking about your topic once you know if the funding posed a potential conflict of interest. The National Center for Responsive Philanthropy both supports progressive philanthropy (its own stated bias) and has documented conservative investment in building an ideological research infrastructure (see $1 Billion Dollars for Ideas).

Unfortunately, researchers also sometimes engage in unethical behavior and do not disclose things that they should. For example, a recent study on COVID-19 (Bendavid et al., 2020)[10] did not disclose that it was funded by the chief executive of JetBlue, an airline company losing money from COVID-19 travel restrictions. It is alleged that this study was paid for by airline executives in order to provide scientific support for increasing the use of air travel and lifting travel restrictions. These conflicts of interest demonstrate that science is not distinct from other areas of social life that can be abused by those with more resources in order to benefit themselves.

COVID-19 is a particularly instructive case in spotting bad science. In a rapidly evolving information context, educators and others were forced to make decisions quickly using imperfect information. The Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, two of the most prestigious journals in medicine, had to retract two studies due to irregularities missed by pre-publication peer review despite the fact that the results had already been used to inform policy changes (Joseph, 2020).[11] At the same time, President Trump’s lies and misinformation about COVID-19 were a grave reminder of how information can be corrupted by those with power in the social and political arena (Paz, 2020).[12]

While you can be assured that articles in reputable journals have passed peer review, that does not always mean they contain accurate information. Articles are often debated on social media or in journalistic outlets. For example, here is a news story debunking a journal article which erroneously found Safe Consumption Sites for people who use drugs were moderately associated with crime increases. After multiple scholars evaluated the article’s data, they realized there were flaws in the design and the conclusions were not supported, which led the journal to retract the article. You can find these controversies in the literature by using a Google Scholar feature we’ve talked about before—’Cited By’. Click the ‘Cited By’ link to see which articles cited the article you are evaluating. If you see critical commentary on the article by other scholars, it is likely an area of active scientific debate. You should investigate the controversy further prior to making any conclusive claims in your literature review.

If your literature search contains sources other than academic journal articles, you’ll need to do a bit more work to assess whether the source is reputable enough to include in your review. Without peer review or a journal’s approval, how do you know the information you are reading is any good?

The SIFT method

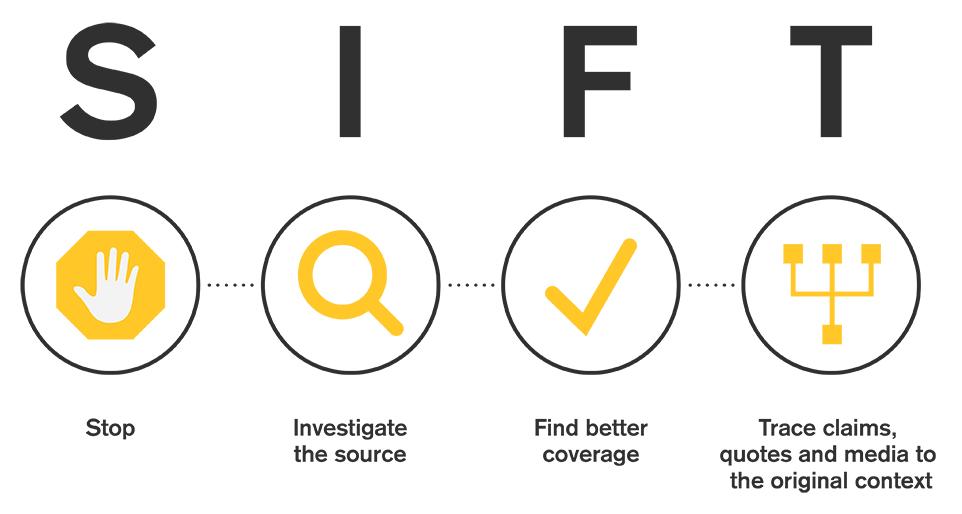

Mike Caulfield from Washington State University and digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention. It is referred to as the “SIFT” method, and it stands for Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context.

Stop

Stop

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable. This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging! What about this website is driving your engagement (positively or negatively)?

Investigate the sources

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source to determine its truth. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of privatized education services, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by a conservative think tank like the Fraser Institute. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the Fraser Institute can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise, positionality, and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. Indeed, one study cited in the video below found that academic historians are actually less able to tell the difference between reputable and bogus internet sources because they do not read laterally but instead check references and credentials. Those are certainly a good idea to check when reading a source in detail, but fact checkers instead ask what other sources on the web say about it rather than what the source says about itself. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating. Not only is this faster, but it harnesses the collected knowledge of the web to more accurately determine whether a source is reputable or not.

Activity: Watch this short video [2:44] for a demonstration of how to investigate online sources. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors. Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find better coverage

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source. The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there.

Activity: Watch this short video [4:10] that demonstrates how to find better coverage and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage.

Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. Secondary and tertiary sources are great for getting started with a topic, but researchers want to rely on the most highly informed source to give us information about a topic. If you see a news article about a research study, look for the journal article written by the researchers who performed the study as citations for your paper rather than a journalist who is unaffiliated with the project.

Activity: Watch this short video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting which demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source. Researchers must follow the thread of information from where they first read it to where it originated in order to understand its truth and value.

Once you have limited your search to trustworthy sources, ask yourself the following questions when evaluating which of these sources to download:

- Does this source help me answer my working question?

- Does this source help me revise and focus my working question?

- Does this source help me address what my professor expects in a literature review?

- Is this the best source I can find? Is this a primary or secondary source?

- What is the original context of this information?

- Is there controversy surrounding this source?

- Are the publisher and author reputable?

At some point, reading another article won’t add anything new to your literature review. Ultimately, the number of sources you need should be guided, at a minimum, by your professor’s expectations and what you need to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on your topic. The purpose of the literature review is to give an overview of the research relevant to your project—everything a reader would need to understand the importance, purpose, and thought behind your project—not for you to restate everything that has ever been studied about your topic.

- Gregory, L. & Higgins, S. (eds.) (2013). Information literacy and social justice: Radical professional praxis. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. ↵

- Booth, C. (2017, November 9). Open access, information privilege, and library work. OCLC Distinguished Seminar Series. Retrieved from: https://www.oclc.org/research/events/2017/11-09.html ↵

- Robinson-Garcia, N., Costas, R., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2020). Open Access uptake by universities worldwide. PeerJ, 8, e9410. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9410. ↵

- RELX (20`19). Annual report and financial statements 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.relx.com/~/media/Files/R/RELX-Group/documents/reports/annual-reports/2018-annual-report.pdf ↵

- Appadurai, A. (2006). The right to research. Globalisation, societies and education, 4(2), 167-177. ↵

- Arunachalam, S. (2017). Social justice in scholarly publishing: Open access is the only way. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(10), 15-17. ↵

- Bali, M., & Caines, A. (2018). A call for promoting ownership, equity, and agency in faculty development via connected learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 46.; Eaves, L. E. (2020). Power and the paywall: A Black feminist reflection on the socio-spatial formations of publishing. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. ↵

- Aguado-López, E., & Becerril-Garcia, A. (2019). AmeliCA before Plan S–The Latin American Initiative to Develop a Cooperative, Non-Commercial, Academic Led, System of Scholarly Communication. Retrieved from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/08/08/amelica-before-plan-s-the-latin-american-initiative-to-develop-a-cooperative-non-commercial-academic-led-system-of-scholarly-communication/ ↵

- Eaves L. E. (2021). Power and the paywall: A Black feminist reflection on the socio-spatial formations of publishing. Geoforum; journal of physical, human, and regional geosciences, 118, 207–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.002 ↵

- Bendavid, E., Mulaney, B., Sood, N., Shah, S., Ling, E., Bromley-Dulfano, R., ... & Tversky, D. (2020, April 17). COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. MedRxiv. ↵

- Joseph, A. (2020, June 4) ↵

- Paz, C. (2020, May 27, 2020). All the President’s lies about the coronavirus: An unfinished compendium of Trump’s overwhelming dishonesty during a national emergency. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/05/trumps-lies-about-coronavirus/608647/ ↵

"a set of abilities requiring individuals to 'recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information" (American Library Association, 2020)

engaging with "the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory & Higgins, 2013, p.ix)

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access

in a literature review, a source that describes primary data collected and analyzed by the author, rather than only reviewing what other researchers have found