13 Definition of Research Paradigms

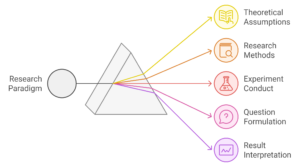

A paradigm is a model. It guides actions and projects pathways and solutions. When we think of a paradigm, if we want to establish a similarity, we must understand that it is like a prism or a lens through which we view reality. This way of observing, and therefore understanding reality, is defined by experience, our frame of reference, our ideology, etc. We all look at our reality from our own perspective, that is, from our paradigm.

Let’s consider a simple example: if your paradigm—your model to follow in everyday social life—is veganism, the way you organize your life, not just your diet but also how you dress, behave, and post on social media, is influenced by that doctrine or model. Thus, our paradigms shape our understanding of reality, but they also relate to our actions.

We all see reality according to the colors of the lens we use to look at it.

In the context of research, the notion of a paradigm defines the what and how of the research. The paradigm guides the questions the researcher asks. The researcher has a pre-existing paradigm or forms one during the research process. Sometimes, a researcher arrives with predetermined ideas, or these are formed through reading literature on the topic and contexts. A useful piece of advice for all researchers is to look critically and question their paradigms. Challenging our own beliefs is a healthy and beneficial process for research.

It is important that any research declares the paradigm it aligns with, as this justifies its assertions and contextualizes the researcher’s system of ideals. Paradigms also distinguish scientific communities, as they validate and reach consensus based on theories, methods, and practices they consider legitimate. Declaring the standpoint from which we will view the context or define categories or codes is a significant step in the methodological coherence of research.

A paradigm is a worldview of knowledge shared by a community of individuals and a model from which to approach reality to understand, interpret, and solve potential problems. A prior step is to acquire sufficient theoretical references on the topics to be researched, and a subsequent step is to define the methods that will be used in the research.

By defining the lens through which we will examine the problem, context, and categories, we are charting a path that allows us to question and define:

- The theoretical assumptions about reality and knowledge.

- What should be observed and examined in scientific research.

- The shared agreements within scientific communities.

- The types of methods and methodologies that are legitimate to use in research.

- How an experiment should be conducted and what equipment or tools are available for it.

- The types of questions that should be formulated to find answers related to the objective.

- How these questions and their respective answers should be structured.

- How the results of the research should be interpreted.

- The set of theories that aim to explain the phenomena of reality.

- The preparation of scientific manuals, both basic and advanced.

The two most studied paradigms are the positivist/post-positivist and the interpretive; however, since the mid-20th century, the critical paradigm has also emerged, and in recent decades, there has been talk of a postmodern paradigm. In some countries like Canada, an Indigenous paradigm is discussed. In addition to the paradigms mentioned, there are many other epistemic and ideological positions that can influence your perception of reality.

On the other hand, it is not only your paradigm that matters; we must consider that the subjects we interact with in the context, community, or institution we are researching also have their own lenses through which they view their environments and processes. This means that when we think about research and ask ourselves questions about why things happen, why a subject thinks or behaves in a certain way, we must realize that often there are issues related to how their worldview is structured. Just as our worldview will allow us to see a part of the context clearly, some issues may remain outside our view. This is completely normal.

What can we do to try to understand the full picture?

Ask, always ask. Question ourselves about our stance and listen to others about their decisions, actions, and ways of seeing life.

Activity

I leave you with a reflective exercise: Write in your notebook some presumption you have. For example, that dogs always chase cats, that older people are more responsible, that having good handwriting is synonymous with being diligent in school, or that people from the new generations do not read enough. Then question, “How do I know this?” “What from my experience makes me think this way?”

We will see some details of these paradigms in the following section.

Epistemic positions refer to the different perspectives or stances that people adopt regarding what is considered knowledge, how it is acquired, and how it is validated. Essentially, they relate to an individual’s or group’s beliefs about the nature of knowledge, truth, and justification. In educational and philosophical contexts, epistemic positions influence how people approach learning, understanding, and research. For example, someone with a positivist epistemic position might prioritize empirical evidence and objectivity, believing that knowledge must be observable and measurable. On the other hand, an interpretive epistemic position might emphasize subjective understanding, valuing context and personal experiences in creating knowledge.

Epistemic positions determine:

What is considered valid knowledge (objective vs. subjective, observable vs. experiential).

How knowledge should be acquired (through experimentation, observation, interpretation, dialogue, etc.).

How knowledge claims should be justified (through empirical evidence, logical reasoning, or other forms of validation).

These positions are central to discussions on research paradigms, scientific approaches, and educational methodologies, as they influence how researchers and educators conceptualize and carry out their work.

Ideological positions in research refer to the frameworks of beliefs, values, and principles that researchers consciously or unconsciously assume, influencing how they approach their work, interpret reality, and what goals they aim to achieve with their research. These positions affect everything from the choice of study topic to the interpretation of results and the formulation of conclusions.

Ideological positions encompass beliefs about how the world should be, what is considered just or unjust, and the social and ethical priorities or commitments of the researcher. In this sense, they go beyond political beliefs and are linked to research paradigms (such as positivist, interpretive, critical, postmodern, Indigenous, among others) and the researcher’s relationship with their object of study and context.

Ideological positions can also include concerns for gaps (social, economic, educational, technological, etc.), gender perspectives, and a focus on vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. These positions influence the selection of topics, methodological approach, relationship with participants, data interpretation, and the purposes to which the research is oriented. Furthermore, they determine how the researcher perceives themselves: as a neutral observer, an agent of change, a dialogue facilitator, a sense-maker, or a defender of rights, among other roles.